Around the world, those of us who have, for half a century and more, questioned and challenged the reining dogma of “growthmania” — the widespread delusion that infinite population and economic growth is possible in a finite ecosphere — are in mourning. It is as if, as Herman’s longtime colleague and admirer William E. Rees remarked, we have all just experienced a “disturbance in the force of ecological economics.” And indeed we have. There has been a tear in the mystic chords of community.

The father of ecological economics has passed away. Herman E. Daly — the pioneering, indefatigible champion of the steady-state economy — died in Virginia on October 28 at the age of 84. He is survived by his wife Marcia — the “love of his life” for nearly 60 years — and by his two daughters Terri and Karen, several grandchildren, and extended family. As his official obituary at the Tribute Archive notes: “Herman’s gentle yet larger than life spirit will be missed terribly by all who knew him and loved him.”

I knew Herman for about a quarter-century, not terribly well, but well enough to know that these sincere words ring true.

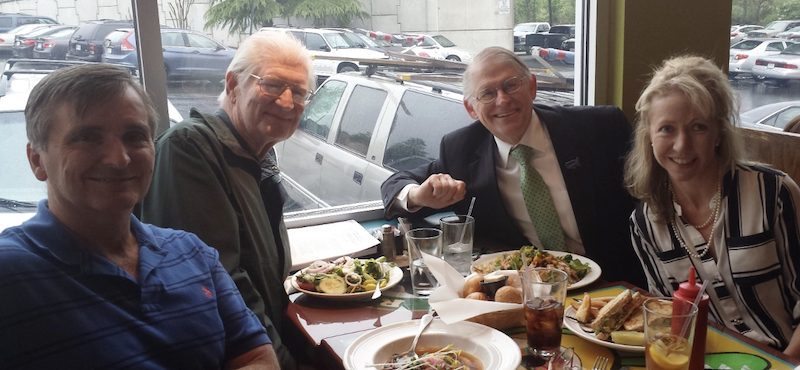

The author (l.) enjoying lunch in 2014 at a diner in Hyattsville, Maryland with Herman Daly and Roy Beck and Anne Manetas of NumbersUSA

NumbersUSA founder Roy Beck had long expressed admiration for Herman’s lifetime body of work to me and likewise, Herman had long mentioned his respect for Roy’s measured and compassionate approach to the fraught immigration issue. In 2014, I was finally able to engineer a lunch meeting in Maryland between these two great men — one the subject of a front-page profile in The Wall Street Journal, and the other a profile in The New York Times. Both were pioneers in their own right. It was a delightful encounter, as the smiles in the photo show.

Roy has another memory of Herman that he wanted to share with NUSA friends and members:

A few days before a 2015 conference on the degradation of the Chesapeake Bay, I was disinvited from presenting Leon’s and my study on habitat in the Chesapeake watershed. Conference organizers said they had to bar me because federal officials said they would withdraw their financial support for the conference if I was allowed to speak about the role of immigration in driving the massive population growth that was threatening any ability to ever restore the Bay.

Federal officials claimed it would be hate speech. So I sat in the audience. During one of the Q&As, Herman Daly, who had earlier given the keynote address to an adoring crowd of conservationists, stepped to the audience mic and expressed displeasure with my silencing. He then used his credibility with unflinching courage to talk of the books and actions of my life and attesting that none justified my treatment by the conference. Nobody asked him to do this. Few then or now have the guts to do such a thing. But he was Herman Daly.”

This is the kind of grateful tribute that Herman Daly’s integrity and memory inspires. In the same vein energy, systems, and sustainability podcaster (“The Great Simplification”) Nate Hagens, a former Wall Street analyst, had spoken to Herman just days before his passing, and mentioned his “erudite, kind, gracious self.” Hagens added: “It’s his grace, and humility, and kindness, and how he interacted with other humans that has influenced more than the intellect….[and yet] he was a real intellectual giant.”

Herman Daly’s Life and Achievements

Born and raised in Texas to hard-working parents (whom Herman described years later as “affectionate and wise”), a grandson of immigrants from Ireland and Germany, he was a shy child drawn to swimming, tennis, and books. In the mid-1940’s, as a tyke of just seven, he was infected by that much-feared scourge of the era — the polio virus — which partially paralyzed and hospitalized him for two months. His left arm never recovered and his left hand atrophied completely; at age 14, his entire left arm was amputated to avoid further complications. About this traumatic and permanent corporeal and emotional loss at such a tender age, Herman later observed: “This painful experience taught me to concentrate on what I am able to do and not waste energy on things that I can’t do.”

Interested in both the humanities and science, Herman decided to major in economics at Rice University in Houston because he believed it was situated at the interface between the natural sciences and biophysical resources on the one hand, and ethics and human goals on the other. What he soon discovered however, to his chagrin, was that this was how classical economists of the 19th century had viewed their profession, not how the growth and model-obsessed neoclassical economists of the 20th and did, and still do today. Ensconced in their bubbles of graphs and abstract production functions, these arcane specialists were all but oblivious to the real-world ecosystems which envelop and delimit all human economies. Disappointed in how his chosen field had devolved, Herman resolved to pursue an academic career in economics after all, but with the aim of restoring biophysics and ethics to their rightful place.

After finishing his B.S. at Rice, Herman was accepted to graduate school at Vanderbilt University in Nashville and began to study economic development in Central America. Among other classes, he took courses in economic theory and statistics from the brilliant Romanian immigrant, Professor Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who in 1971 authored the landmark tome The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, which showed how economic systems were inextricably tethered to the second law of thermodynamics.

Upon completing his doctorate at Vanderbilt, from 1968 to 1988 Herman taught economics at Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge. It was at LSU that he first began to explore environmental economics (as distinct from ecological economics), which at least considers rather than ignores the natural environment and resources. It is to environmental economics that we owe, for example, the concept of “externalities”, that is, environmental costs and benefits of production and consumption activities not captured in market transactions.

In 1968, Herman was invited to be a guest professor by the Federal University of Ceara in Brazil, through a project underwritten by the Ford Foundation in this impoverished region. The next year, as a researcher at Yale, he received his first formal exposure to the population issue when he conducted demographic research on population and economic growth in northern Brazil; as part of this research he examined both Malthusianism and Marxism in the Brazilian context.

It was through his teaching and research in Brazil that Herman began to understand that population growth both increased poverty and exacerbated income disparities between haves and have-nots. During this era, he also reread classical economist and political philosopher John Stuart Mill’s landmark 1848 essay “Of the Stationary State” in his Principles of Political Economy, containing these prescient ideas, which spoke profoundly to Herman:

There is room in the world, no doubt, and even in old countries, for a great increase of population, supposing the arts of life to go on improving, and capital to increase. But even if innocuous, I confess I see very little reason for desiring it….

It is not good for man to be kept perforce at all times in the presence of his species. A world from which solitude is extirpated, is a very poor ideal…

Nor is there much satisfaction in contemplating the world with nothing left to the spontaneous activity of nature; with every rood of land brought into cultivation…all quadrupeds or birds which are not domesticated for man’s use exterminated as his rivals for food…and scarcely a place left where a wild shrub or flower could grow without being eradicated as a weed in the name of improved agriculture.

If the earth must lose that great portion of its pleasantness which it owes to things that the unlimited increase of wealth and population would extirpate from it, for the mere purpose of enabling it to support a larger, but not a better or a happier population, I sincerely hope, for the sake of posterity, that they will be content to be stationary, long before necessity compels them to it.”

It was John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) who first advanced the concept of the steady-state economy in the mid-1800s, one in which both capital and population would be maintained at a stable size. Mill was clearly far ahead of his time, and more than a century later, Herman made it his own life’s work to reintroduce and champion these venerable, timeless ideas and ideals to modern audiences in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, at a time when the bloated human enterprise pressed far harder against — or even exceeded — environmental limits than it ever had in the time of Mill. As Daly described it, we now live in an ever more “full world.” Or as the English rock band The Who sang rather more provocatively in their 1978 song “Had Enough”: “…the world’s gonna sink with the weight of the human race.”

Mill and his intellectual descendant Daly took pains to emphasize repeatedly that a stationary condition of capital and population need not imply a stationary or stagnant state of human improvement. There would be as much room as ever for intellectual, cultural, moral, and social progress. As Herman phrased it: “as much room for improving the Art of Living and much more likelihood of it being improved, when minds cease to be engrossed in the art of getting on.”

In the early 1970s, Herman’s increasing body of pioneering work — so refreshingly contrary to the growth-preoccupied creed of the dominant school of neoclassical economics — began to attract the wider attention of ecologists, environmentalists, systems analysts and other scientists and policymakers. He edited an anthology called Towards a Steady-State Economy, published in 1973, which was well received. He was cited in the landmark, paradigm-shifting book The Limits to Growth, published in 1972 by MIT systems researchers on behalf of the Club of Rome. He wrote and spoke prolifically, and his trenchant and perceptive critiques of unsustainable growth-based economies — deriding the buzzword of “sustainable growth” as an oxymoron, promoting the term “uneconomic growth” — began to be quoted and cited in all manner of books, articles, fliers, speeches, and scholarly papers.

By 1996, Herman had attained enough prominence that he was the subject of a long, front-page profile in The Wall Street Journal, for which I insist on claiming a modicum of credit for plugging him to Journal reporter G. Pastel Zachary, who authored the story. Zachary began:

Questioning growth is heretical to most Americans. Economists, in particular, believe that growth is the answer to most of the world’s problems. So when Herman Daly, a professor at the University of Maryland, dared to challenge the assumption, he was dismissed in academic circles. But these days, more economists are warming to his theory that the world economy — and global consumption — must eventually stop growing if nature is to survive.”

Zachary quoted Stanford University economist Lawrence Goulder:

Folks like Herman Daly are correct in criticizing the practice of economics. They are having an impact by getting more economists to actually take account of the environment and natural resources.”

On the other hand, Zachary emphasized, Daly’s ideas continued to provoke skepticism (if not outright scorn) among other eminent mainstream economists, such as MIT’s Nobel laureate Robert Solow, who said he was “deeply suspicious” of Daly and considered him an alarmist on the question of resource scarcity.

But we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves. Back in 1988, Herman left LSU for a six-year stint as a senior economist in the Environment Department at the World Bank, where he was hired over the opposition of certain other employees. Later, capping a 40-year teaching career, he became a professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy, educating a new generation of students more receptive to his heterodox ideas than the stodgy World Bank had been.

While at the World Bank, Herman assessed the environmental and economic impacts of proposed projects in Latin America. At a more theoretical level, he proposed three basic rules or criteria for evaluating prospective Bank loans:

As rational as these criteria might appear in a sane world with a long-term view, they were criticized within the World Bank because it was thought they would delay badly needed economic growth and make it harder to approve loans for development projects such as dams and roads.

Herman also designed his “ultimate means to ultimate ends” pyramid, which graphically illustrates the roles of natural capital and economic growth in contributing to human wellbeing.

Throughout his career, Herman worked overtime as an activist to build broader public and academic support for ecological economics and the steady-state economy. With Robert Costanza and others, he co-founded the International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE) in the mid-eighties. ISEE publishes the journal peer-reviewed journal Ecological Economics, established in 1989. In 2003, with wildlife biologist Brian Czech, Herman cofounded the Center for the Advancement of the Steady-State Economy (CASSE).

Herman’s achievements and accolades are too numerous to list in their entirety, but include developing (with John Cobb) the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), which they proposed as a more valid indicator of sustainable development than the GDP. He was the recipient of the Honorary Right Livelihood Award, the Heineken Prize for Environmental Science from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Sophie Prize (Norway), the Leontief Prize from the Global Development and Environment Institute, and the Blue Planet Prize of the Asahi Glass Foundation. And I can’t count how many times over the years I have heard the comment that in a more rational world with more ecologically-informed economists, Herman would have received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Herman Daly on Population, Immigration, and the Environment

With regard to population, for Herman it was not an either/or proposition. In the late 1990s, I was in the audience as Herman participated as one of four panelists at an event about population on Capitol Hill (i.e., in one of the U.S. Congress buildings). It was sponsored by one of the veteran American population NGO’s, the Population Council. Each of the panelists delivered some opening remarks and then there was some back and forth and questions from the audience.

One of the questions from the audience asked a different panelist about the causal role of population in America and the world’s environmental predicament. It prompted her to comment that population growth really had very little to do with environmental degradation. It was a red herring.

Overconsumption was the real problem. She looked over to Herman and said, “Right?” Herman smiled back cordially at her and said, in effect, nope, not right. He then proceeded to ennumerate ways in which population was indeed problematic for the environment. Then he talked about how for decades, ecologists, economists, and others, had debated whether population or consumption bore responsibility for damaging the environment. Herman stated emphatically that for him, this was as sterile and pointless as debating whether it is the width or the length of a rectangle that is responsible for its area. They both are. One multiplies the other to determine the overall area. And so it is with population and consumption in determing the extent of environmental impacts. They each play a role.

Towards the end of his life, in 2016, Herman summarized his views on population in an article in the journal Solutions, where he endorsed ten specific policy proposals for moving to a steady-state economy. Number nine in that list was this:

Stabilize Population. We should be working toward a balance in which births plus in-migrants equals deaths plus out-migrants. This is controversial and difficult, but, as a start, contraception should be made available for voluntary use everywhere. And while each nation can debate whether it should accept many or few immigrants, and who should get priority, such a debate is rendered moot if immigration laws are not enforced. We should support voluntary family planning and enforcement of reasonable immigration laws, democratically enacted. A lot of the pro-natalist and open-borders rhetoric claims to be motivated by generosity, but it is “generosity” at the expense of the U.S. working class—a cheap labor policy. Progressives have been slow to understand this. The environmental movement began with a focus on population but has frequently given in to political correctness.

For population activists like myself, there were few allies of Herman’s stature as dependable as he was over the years. In 1998, I was deeply embedded in a bitter internecine war for the soul of the Sierra Club on the issue of U.S. population stabilization and environmental sustainability. In previous years, the Club and its Population Committee had been infiltrated and taken over by proto-Woke activists who smeared anyone who linked population growth (to say nothing of mass immigration) with environmental harm as a racist, nativist, xenophobe, and probably a eugenicist to boot. This cabal overturned the Club’s longstanding positions in support of U.S. population stabilization and the level of immigration restriction needed to achieve that.

In response, a grassroots group called Sierrans for U.S. Population Stabilization (SUSPS) organized to gather the number of Sierra Club members’ signatures needed to force a referendum of the Club-wide membership on the issue. We gathered those signatures and managed to put a question on the ballot for the spring 1998 annual elections. I was very active in SUSPS, and later, when we decided to approach well-known individuals to see if they would publicly lend their names to our side in what had become a very divisive, ugly campaign, I called up Herman to see if I could enlist him. It didn’t take any persuasion on my part. He was with us all the way, in spite of arm-twisting and threats by the Sierra president and board to get these public signatories to drop off. Several did. Herman did not. He was resolute.

A Final Tribute and Farewell

I will close by quoting my own mentor and old friend, Professor William E. Rees of the University of British Columbia, creator of the ecological footprint concept and co-developer of ecological footprint analysis. When he heard of Herman’s death, Bill wrote:

Herman Daly was the most stimulating yet innocently exasperating of mentors. Through the late 1970s and 1980s I was beginning to understand mainstream economics (long after my siloed PhD in ecology) and how it could be used to block progress toward ecologically sensible planning. I began to formulate concepts and counterarguments to fill the gaps and along the way discovered Herman Daly.

Inspiringly brilliant but ego-bustingly frustrating! For each of my nascent notions on how to fix economics and reconcile it with basic ecology, I found that Herman had got there first, much better and vastly more eloquently.

I was delighted to have finally met Herman and tell him so personally in a one-on-one lunch at the 1992 ISEE Conference in Stockholm (where I also introduced ecological footprint analysis). For the past three decades, he has been a reliably consistent source of advice and encouragement.”

Finally, I would be remiss if I did not mention that Herman’s religious faith played a big part in his ethics and worldview. He was a devout Christian his entire life. One gets a sense of his core decency, goodness, and priorities from a passage in his official obituary:

Herman was foremost a teacher and mentor. He loved engaging with students and peers, learning from all disciplines. Grounded in a deep faith, he was above all a kind and humble man: a dedicated and loving son, brother, husband, father and grandfather. He had a long and illustrious career as a groundbreaking leader in Steady State Economics, and a founding member of the international field of Ecological Economics. His career led him to many locations, including Brazil, Yale University, Louisiana State University, the World Bank in Washington, D.C., and the University of Maryland. Throughout this career, he was always engaged with many great thinkers and colleagues from around the world, all dedicated to the survival and preservation of our beautiful planet, God’s creation.

Amen and Godspeed, Herman.

LEON KOLANKIEWICZ is the Scientific Director for NumbersUSA and vice-president of Scientists and Environmentalists for Population Stabilization