Over the past twenty-five years, NumbersUSA has published numerous scientific reports on the causes and consequences of sprawl in the United States. Our most recent study quantifies ecological decline in the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed over the past three decades. Looking forward, we explore a path toward ecological sustainability centered on stabilizing the region’s population through reduced immigration.

An estuary is an aquatic environment, one where freshwater from the land and saltwater from the sea mingle and mix. Chesapeake Bay is America’s largest and most productive estuary. The bay’s watershed supplies all of its freshwater. Any pollutants from city streets, factory outfalls and farm fields are transported and dumped into the bay to its detriment.

The Chesapeake Bay Watershed includes portions of six states on the East Coast

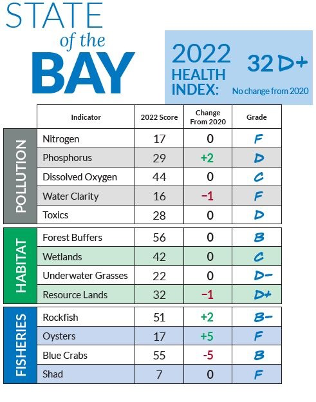

When the Chesapeake Bay Foundation last issued a “report card” on the State of the Bay in 2022, it slapped the bay with an overall grade of D+, a stinging indictment of declining ecological health.

A more recent report card on the Bay and its watershed, released last year by the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science, upgraded the Bay’s condition to a C, while the watershed received a C+. Still not exactly a ringing endorsement of the region’s ecological health.

The most important determinants of the Bay’s health are human numbers and the amount of economic activity taking place in the watershed. The latter includes proliferating land development to accommodate a population burgeoning caused by immigration into the region. This is confirmed in a new study just published by NumbersUSA: Watershed Woes: Population Growth and Sprawl Degrade the Chesapeake Bay and Its Watershed.

In analyzing water quality, “loadings” refer to the total mass of pollutants discharged into a water body. Similarly, we can refer to large and growing human populations as imposing a growing ecological load or burden on an ecosystem.

The population of the Chesapeake Bay watershed grew rapidly between 1982 and 2017, from 16 to 22 million. And in those thirty-five years, attendant new development — subdivisions, strip malls, office parks and so forth — claimed more than 5,000 square miles of natural and agricultural lands in the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed. These losses total about twice the area of Delaware.

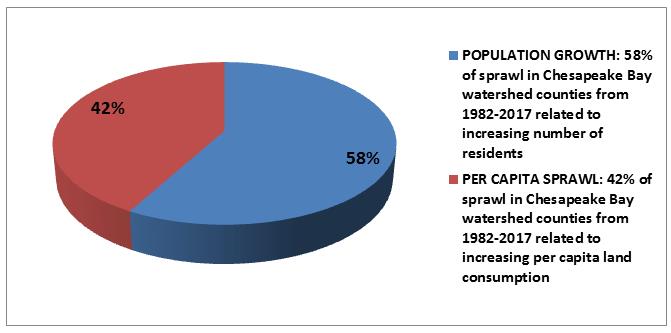

Our study shows that population growth accounted for 58% of this sprawl, with increased per capita land use accounting for the remainder. Increasing human numbers accounted for an even higher percentage of more recent (2002-2017) sprawl: fully 71 percent.

How has this land conversion and development affected Chesapeake Bay? Simply put, more people equals less habitat for other species and thus declining wildlife populations. More people also means more air and water pollution.

Natural landscapes covered with trees and other vegetation generate virtually no pollutants. In contrast, sprawling human developments include:

The damaging effects on Chesapeake Bay’s water quality and aquatic life start right with clearing land for new development to support the burgeoning population within the watershed

The government-funded, inter-agency Chesapeake Bay Program states clearly: “The Chesapeake Bay region’s rapid population growth has raised concerns over whether the watershed can continue to sustain the plants, animals and people that live there.” But area activists and environmental managers mostly refuse to acknowledge the primary driver of their region’s ecological decline.

For example, the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science 2025 report card only mentions population growth once — in the context of increasing “freshwater salinization” as a result of the increasing use of road salts to melt snow and ice. And why is more salt being applied to road surfaces in the watershed? Because of increasing traffic volumes and an increase in paved road surfaces, driven, of course, by an increasing population.

By forthrightly addressing population and its mass immigration driver, NumbersUSA’s new study fills an important gap left by the incomplete analyses of government agencies and conservation organizations. Taken to heart, its message could help area environmentalists actually succeed in saving Chesapeake Bay, rather than just slowing its inevitable demise. Visit the study’s website to learn more!